Understanding Focal Motor Seizures: Kathy’s Story

This post explores focal motor seizures. It discusses how they start, how they feel, and how they affect people’s lives. Through the story of Kathy, a young woman who discovers she has this type of seizure, we hope to shed light on the sometimes subtle, sometimes dramatic ways seizures can appear. Finally, I’ll explain how focal motor seizures are classified, what causes them, and how people manage them, not just medically, but with everyday adjustments and hope for living well.

Dr. Clotilda Chinyanya

11/28/20258 min read

Kathy’s Story

Kathy is 24. She works as a junior interior designer at a small team-run design firm in her city. She’s cheerful, energetic, known for her eye for patterns and colors, always sketching floor plans or mood boards on her tablet. On weekends she paints murals, goes for afternoon runs, or meets friends for coffee.

But over the past few months, she began having strange episodes that are subtle, confusing, and unsettling. The first time, she was at her drafting table working on a layout, when suddenly she felt her right hand twitch. It started with a tiny jerk in her index finger, which she dismissed as a cramp. Then the twitch slowly spread: her hand jerked rhythmically, the fingers closing and opening repeatedly. It felt like a muscle she couldn’t control. At the same time, an odd sensation washed over her like a rising electric tingling in her arm.

She sat there, frozen. For maybe 30 seconds, she couldn’t stop the movement. Then it subsided, leaving her hand limp and shaky. She blinked, startled, and looked around. Her coworker glances over with concern; he asked if she was okay. She nodded, but inside she felt disoriented like she had just come back from somewhere. She couldn’t clearly remember exactly what she had been drawing. She shrugged it off as fatigue or stress.

A few days later, a similar thing happened, while she was waiting in line at a coffee shop. Her lower lip twitched, then her hand started moving, as though she was tapping on a keyboard. She felt weird, distant, and unsure. The barista asked if she was okay. She gave a blank smile and quietly stepped out, clutching her latte. Later that day, her arm ached. She felt exhausted.

Then one evening, she was home, watching a show, and noticed her left foot begin to jerk rhythmically. The movement lasted longer this time, nearly a minute. Her heart raced. Afterward, the foot felt weak and tingly. She couldn’t stand comfortably for hours. That scared her.

When yet another similar event happened, but with both her right hand and right face twitching at once, she decided to seek medical advice. She saw a neurologist. After a detailed clinical history, an EEG, and an MRI, she learned she had recurring focal motor seizures. The doctor explained that the seizures started in a very specific area of her brain: the part that controls movement for the affected limbs.

She felt relieved and scared at the same time. What did this diagnosis mean for her job, her art, her life? Over the next months, with anti-seizure medication and some lifestyle adjustments, she learned to manage the seizures and gradually regained a sense of control.

Kathy had come to understand an important truth: seizures aren’t always dramatic convulsions. They can be small, strange moments. And they matter just as much.

Understanding Focal Motor Seizures

What are focal seizures and how do motor seizures fit in?

Seizures come in many forms. According to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification, a core distinction is where in the brain a seizure begins. If the abnormal electrical activity is localized, meaning it begins in a specific area of one hemisphere, it is called a focal onset seizure.

Within focal seizures, there is a further split based on awareness: some seizures happen while a person remains conscious (focal aware), while others cause impaired awareness (focal impaired awareness).

Also, seizures may be classified by what kind of symptoms they produce at onset: they may show motor features (movements, muscle changes) or non-motor features (sensory, emotional, cognitive, autonomic).

A focal motor seizure is a seizure whose first prominent manifestation involves changes in muscle tone, movement, or posture. If the seizure also impairs awareness, it may be called a “focal motor seizure with impaired awareness” (see Dante’s Story). In other words, motor symptoms with altered awareness is what many people think of when they imagine epilepsy but focal motor seizures are far more varied and subtle than stereotypical convulsions.

Different types of focal motor seizures

Focal motor seizures come in a spectrum of movement-types. Some of the main types include:

Clonic: rhythmic, repeated jerking of a muscle group (for example, a twitching hand, limb, or facial muscles).

Tonic: sudden stiffening or increased muscle tone, lasting seconds to minutes.

Myoclonic: quick, brief jerks like lightning-fast twitches.

Atonic (or negative motor): sudden loss or reduction of muscle tone. A limb may go limp.

Dystonic / posturing seizures: sustained abnormal contractions of muscles, producing odd postures or twisted positions.

Focal motor seizure with paresis/paralysis: sudden weakness or complete loss of movement in a specific muscle group, causing the affected limb or area to become briefly immobile.

Focal epileptic spasms: rapid, brief flexion or extension movements of the trunk or proximal limbs, often occurring in short, repeated clusters lasting 1–2 seconds each.

Focal hyperkinetic seizure: bursts of large, irregular, high-energy movements such as thrashing, pedaling, rocking, or pelvic thrusting, typically involving the torso or proximal limbs.

Focal motor seizure with dysarthria/anarthria: impaired coordination of speech muscles leading to slurred, strained, or unintelligible speech while language comprehension and expressive ability remain intact.

Focal motor seizure with negative myoclonus: a sudden, very brief drop in muscle tone (less than 500 milliseconds) causing a limb or the head to dip, sag, or overshoot its position without any preceding jerk.

Focal motor seizure with version: forceful, sustained turning of the eyes, head, or trunk to one side, with the direction of deviation helping indicate the seizure’s originating hemisphere.

Focal bilateral motor seizure: seizure activity rapidly spreads from one hemisphere to activate muscles on both sides, often producing asymmetric postures such as a “fencer’s posture” or “figure-of-4,” and may still occur with preserved awareness.

Focal automatism seizure: repetitive, coordinated movements that look voluntary but happen without conscious control; these often accompany impaired awareness but can also appear when the person is still aware. They are further described as follows:

o Orofacial automatisms: involuntary mouth or facial movements such as lip-smacking, chewing, swallowing, clicking, or rapid blinking.

o Manual automatisms: repeated hand actions — fumbling, tapping, rubbing, manipulating objects, or exploratory hand movements (one or both hands).

o Pedal automatisms: rhythmic or patterned leg and foot movements, such as pacing, stepping, or light walking motions; smoother and less intense than hyperkinetic activity.

o Perseverative automatisms: continuing the movement or task the person was doing right before the seizure, even when it no longer makes sense.

o Vocal automatisms: involuntary sounds like grunts, hums, or brief noises.

o Verbal automatisms: repeated words, short phrases, or simple speech that happens automatically.

o Sexual automatisms: involuntary behaviors with a sexual or intimate quality.

o Other automatisms: a variety of automatic actions such as head nodding, removing clothing, or other repetitive, purposeless movements.

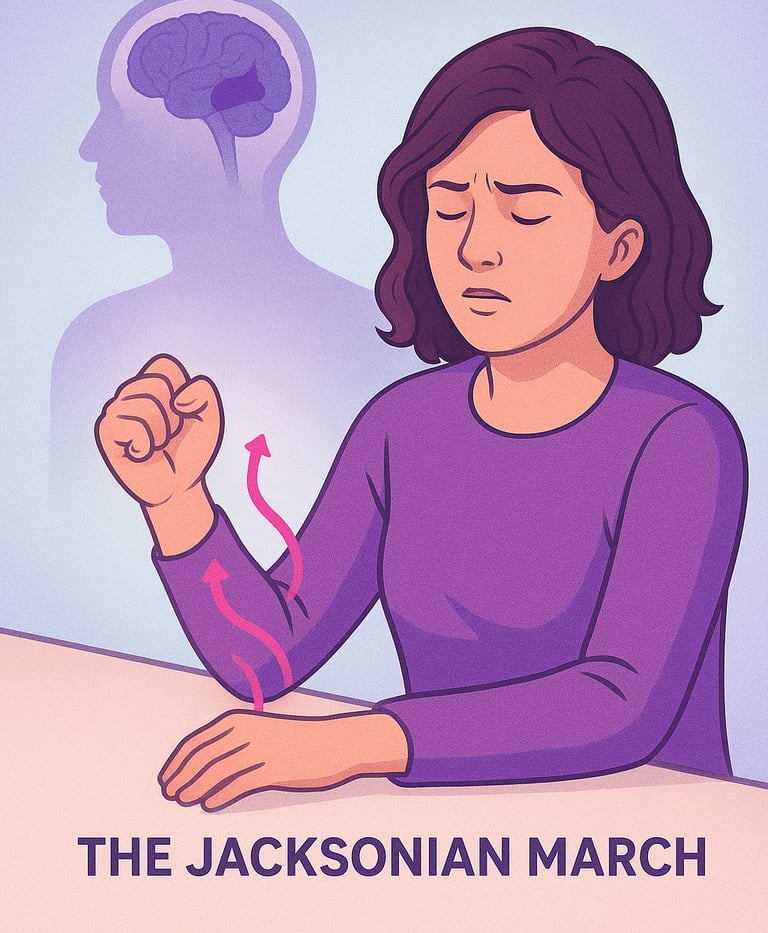

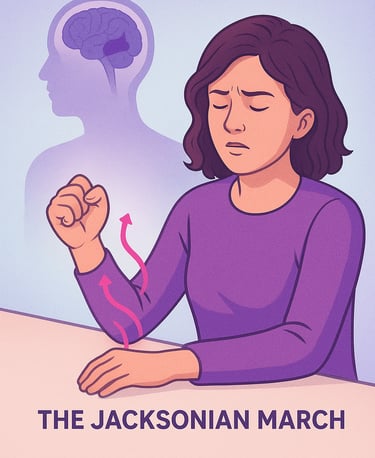

Because the seizure begins in a specific “motor area” of the brain (often the region called the precentral gyrus, or primary motor cortex), the symptoms typically appear in the part of the body controlled by that region, often a limb, face, or part of a limb. The muscle groups farther from the body’s center are usually affected, for example, the hands, fingers, or face, rather than larger muscles of the legs or trunk. In some cases, the movement stays localized; however, in other cases, it can “march” spreading gradually to adjacent body parts in a pattern known as a Jacksonian march. For instance, a seizure might start with a twitch in a finger, then move up to involve the hand, arm, and even face on the same side.

After a focal motor seizure, some people may experience a temporary weakness or paralysis in the affected muscles, a phenomenon known as Todd paralysis. The weakness may last for minutes or hours.

Sometimes focal motor seizures remain confined to one side of the body; other times they evolve into more widespread seizures, what’s called a focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (previously “secondary generalized”). That’s when abnormal electrical activity spreads from the focal area to involve both hemispheres of the brain.

What Causes Focal Motor Seizures and How Are They Diagnosed?

Because focal seizures, including motor types, start in a specific part of the brain, their cause can often be traced to either structural issues or certain syndromes/conditions. Depending on the individual case, possible causes include brain injuries, developmental abnormalities, infections, scarring, tumors, strokes, or congenital predispositions. In a significant number of cases, however, no clear cause is found. The seizures may arise from an “idiopathic” focus (i.e., a focus without an identifiable structural lesion or external trigger).

To make a diagnosis, neurologists rely primarily on clinical history, observation of the seizure events (when possible), and specialized tests:

Electroencephalogram (EEG): to detect abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

Neuroimaging (often MRI): to see if there are structural abnormalities e.g. scarring, tumors, malformations.

These tools help doctors localize the seizure focus (i.e., the part of the brain where seizures begin) and decide on the appropriate management plan.

How Focal Motor Seizures Feel and Affect Life More Than Just “Convulsions”

One of the most important points about focal motor seizures is that they don’t always look dramatic. Unlike the stereotypical generalized tonic-clonic seizures (with whole-body convulsions), focal motor seizures can be subtle: small jerks, twitches, brief stiffening, or automatisms. Those slight hand movements, a fleeting facial twitch, they all count.

For some people, these seizures are easy to miss, or to misinterpret as nervous tics, fatigue, stress, or random muscle spasms. Others may feel confusion, disorientation, or even faint awareness of what’s happening. Especially when awareness is impaired, the person might not realize they are having a seizure at all or may not remember it clearly. That makes diagnosis harder.

Because of that, people with focal motor seizures may go long periods without being diagnosed; their symptoms may seem “benign” or inconsequential to outsiders, but for the person experiencing them, they can be distressing, exhausting, and unpredictable. As in Kathy’s story, those small, puzzling events disrupted her sense of self, her work, even her trust in her own body. But over time, these subtle seizures may build up, occurring more often, affecting work, social life, confidence, and emotional well-being. If the seizure focus spreads, or if the seizures evolve into bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, the risk and impact can grow significantly.

Treatment, Management & Life with Focal Motor Seizures

The good news is that many people with focal motor seizures respond well to treatment. The first-line therapy is often anti-seizure (anti-epilepsy) medications, can significantly reduce the frequency and severity of seizures or eliminate seizures when properly prescribed and monitored.

But medicine is just one part of the picture. Because focal seizures can be unpredictable and subtle, education, awareness, and lifestyle adjustments become equally important. For instance:

Keeping a seizure diary to track frequency, triggers, and patterns (time of day, stress, sleep, diet, etc.).

Creating safer environments (e.g. avoiding dangerous activities when seizures are frequent, ensuring support or supervision when needed).

Maintaining healthy habits: good sleep, stress management, avoiding known triggers.

Being open with friends, family, coworkers, helping them understand what’s happening and how to respond if a seizure occurs.

In some cases, if seizures don’t respond to medications or if there is an identifiable structural cause, other options may be considered, like nerve stimulation, diet therapy, or surgery.

Most importantly, with support and proper treatment, many people with focal motor seizures like Kathy can lead full, meaningful lives. The seizures may no longer dominate their identity.

Why Focal Motor Seizures Deserve More Attention

Because they’re often subtle and varied, focal motor seizures are frequently under-recognized, under-reported, or misunderstood. People may feel isolated, uncertain, or embarrassed. Medical professionals may overlook them or mislabel them as tics, stress, or psychological issues.

But these seizures are real. They affect the brain. They can evolve. If left untreated, they carry risks including seizure worsening, spreading, or even turning into generalized seizures that carry greater danger. Raising awareness among patients, caregivers, coworkers, and the public is crucial. Understanding helps build empathy, reduce stigma, and encourage early recognition and treatment. Stories like Kathy’s that are simple, human, relatable help make that understanding possible.

Final Thoughts

If you or someone you know experiences unexplained muscle twitches, jerks, or strange, brief episodes of movement, especially if they repeat, or if there’s a sense of disorientation, fatigue, or post-event weakness, it may be worth talking to a neurologist. Focal motor seizures aren’t always dramatic. They often hide in plain sight. But with the right attention and care, they don’t have to define a life.

For Kathy, the diagnosis was the beginning of a journey but not the end of her creativity, her confidence, or her dreams. With treatment, support, and awareness, she kept designing, painting, and living.

References & Further Reading

Types of Seizures CDC

Focal seizure MedlinePlus

The New Classification of Seizures by the International League Against Epilepsy (2017) PubMed

Focal Motor Seizures ILAE

Epilepsy and Seizures: What is a seizure? NINDS

Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Types of Seizures.” Overview of seizure types, causes, and treatments Johns Hopkins Medicine

Focal Seizure: What It Is, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment.Cleveland Clinic

Seizure Disorders MSD Manual

Choose Knowledge: