Understanding Frontal Lobe Seizures: When the Brain’s Control Center Misfires

Frontal lobe seizures are among the most misunderstood and frequently misdiagnosed seizure types. Because they can look dramatic, bizarre, or even behavioral, sometimes involving shouting, thrashing, laughing, sudden posturing, or abrupt movements, they are often mistaken for sleep disorders, panic attacks, psychiatric conditions, or non-epileptic events. Yet these seizures arise from the largest and most complex part of the brain: the frontal lobes, which govern movement, speech, behavior, personality, and decision-making. This blog explores what frontal lobe seizures are, how they present, why they are so often confused with other conditions, and how they are diagnosed and treated. Through the story of Ruth, we bring the clinical facts to life and offer clarity, validation, and understanding for people living with these seizures and those who support them.

Dr. Clotilda Chinyanya

12/3/20256 min read

Ruth’s Story: Explosive Nighttime Episodes

Ruth was 34, a high school guidance counselor, known for her calm presence and thoughtful listening. She was the person students went to when life felt overwhelming. When her husband first told her she had been “screaming in her sleep,” she laughed it off.

“It must’ve been a nightmare,” she said.

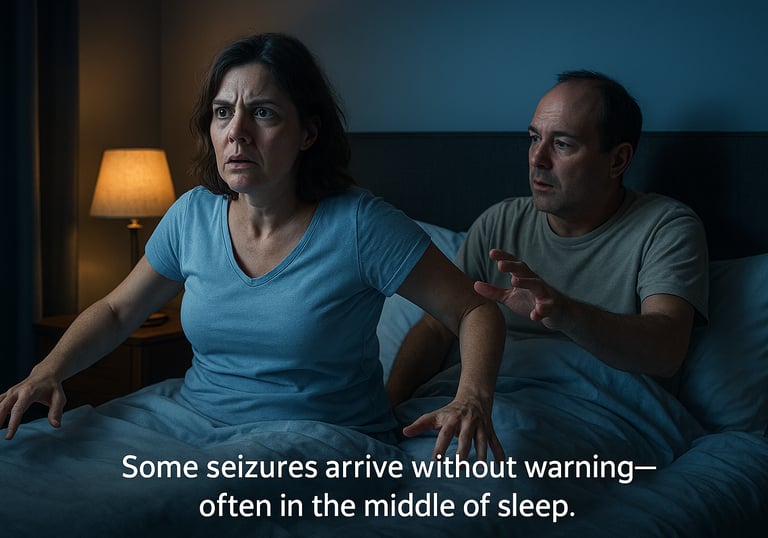

But it kept happening. At first, it was small things. Ruth would bolt upright in bed about 20 minutes after falling asleep. Sometimes she made a loud sound, half shout, half gasp. Other times, her arms would stiffen in an odd posture, one bent, the other extended, as if she were frozen mid-motion. The episodes were brief, often lasting less than 30 seconds. By the time her husband reached for her, it was over. Ruth would lie back down and fall asleep almost immediately.

In the morning, she remembered nothing. As weeks passed, the episodes began to cluster. Two or three in one night. Then nights without any. Her husband started sleeping lightly, afraid to miss one. He recorded a video on his phone to show her. When Ruth watched it, her stomach dropped.

“That doesn’t look like me,” she said. “It looks… fake. Like I’m acting.”

During the day, new things began happening. Once, during a staff meeting, Ruth suddenly stopped speaking mid-sentence. Her head turned sharply to the left. Her right arm stiffened, her hand clenched. A low groan escaped her throat. The entire episode lasted less than a minute. When it ended, she was fully awake, aware, but embarrassed, flushed, and shaken.

“I’m fine,” she insisted, even as her heart raced. “I just… lost my train of thought.”

Coworkers suggested stress. One asked gently if she was having panic attacks. Another mentioned sleepwalking. A doctor initially suggested anxiety and poor sleep hygiene. None of it helped.

It wasn’t until Ruth was referred to a neurologist and admitted for overnight video-EEG monitoring that the pieces finally came together.

“These are frontal lobe seizures,” the neurologist explained. “They’re brief, sudden, often nocturnal, and they can look very dramatic. But they’re not psychological. They’re neurological.”

Ruth cried, not from fear, but from relief.

“There’s a name for it,” she said. “And I’m not imagining it.”

Understanding Frontal Lobe Seizures

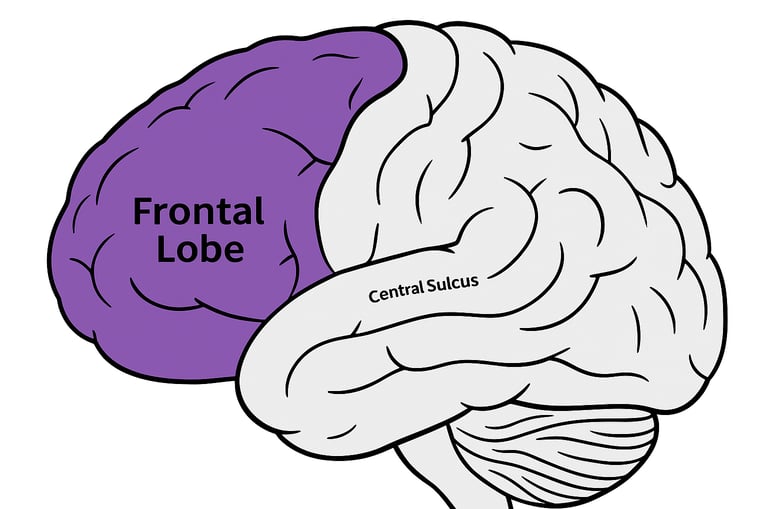

Frontal lobe seizures are a type of focal seizure, meaning they begin in one specific area of the brain. In this case, they originate in the frontal lobes, located behind the forehead. See image below:

The frontal lobes are responsible for many essential functions, including:

Voluntary movement

Speech and language production

Emotional regulation

Behavior and personality

Planning, judgment, and decision-making

Because the frontal lobes are so large and highly interconnected, seizures arising from them can spread rapidly and produce a wide range of symptoms within seconds.

Different Types of Frontal Lobe Seizures

The frontal lobe contains multiple functional regions, and seizures can look different depending on where they start.

· Primary Motor Cortex Seizures

These seizures often cause focal motor symptoms such as jerking, stiffening, or twitching in one part of the body. The movements represent the ‘Jacksonian march” from one area to another, reflecting spread across the motor cortex.

· Supplementary Sensorimotor Area (SMA) Seizures

These are characterized by sudden, asymmetric tonic posturing often one arm extended while the other flexes. Loud vocalizations or speech arrest may occur. Awareness is frequently preserved.

· Orbitofrontal Seizures

These seizures may involve impaired awareness, automatisms, autonomic changes, or unusual smells and sensations.

· Frontopolar Seizures

People may experience forced thoughts, sudden falls, head and eye turning, or axial movements.

· Dorsolateral Frontal Seizures

Seizures in or near speech areas may cause sudden aphasia or difficulty speaking, even while the person remains awake and responsive.

· Cingulate Cortex Seizures

These may involve emotional changes, autonomic symptoms, automatisms, and sometimes laughter (gelastic seizures).

· Fronto-Parietal Opercular Seizures

Symptoms can include mouth and tongue sensations, drooling, speech difficulty, swallowing movements, and emotional or autonomic features.

Key Features of Frontal Lobe Seizures

Frontal lobe seizures have hallmark features that help distinguish them from other seizure types, while also explaining why they are so often misinterpreted.

· Brief and Explosive Onset: These seizures are typically very short, often lasting under 30 seconds, and rarely longer than one to two minutes. They tend to begin abruptly, without the gradual buildup seen in some other focal seizures.

· Sudden Onset, Resolution and Rapid Recovery: The seizures begin and end abruptly. Many people recover almost immediately after a frontal lobe seizure, with little to no postictal confusion. This rapid return to baseline can make events seem voluntary or behavioral, even though they are not.

· Prominent Motor Activity: Motor features are often striking and may include:

o Asymmetric tonic posturing

o Thrashing or fighting movements

o Bicycling or kicking of the legs

o Pelvic thrusting

o Sudden falls

These movements can appear chaotic, but they are usually stereotyped, meaning they look very similar from seizure to seizure in the same individual.

· Vocalization and Speech Changes: Frontal lobe seizures frequently involve vocal symptoms such as:

o Shouting or screaming

o Groaning or grunting

o Sudden speech arrest

o Repetition of sounds or words

o Inappropriate laughter or crying

When seizures involve language-dominant regions, speech may be disrupted even when awareness is preserved.

· Preserved or Impaired Awareness: Awareness during frontal lobe seizures varies. Some individuals remain fully aware and can recall the event, while others have impaired awareness but regain it quickly. This variability contributes to confusion with absence seizures or psychiatric conditions.

· Nocturnal Predominance and Clustering: Frontal lobe seizures often occur during sleep, particularly within the first half-hour after falling asleep or during brief awakenings. They may happen throughout the night rather than at a single sleep stage and frequently occur in clusters, increasing the risk of injury and exhaustion.

Symptoms of Frontal Lobe Seizures

The symptoms of frontal lobe seizures depend on the exact region of the frontal lobe involved and how quickly the seizure spreads.

Motor Symptoms

Sudden stiffening or jerking of one or both sides of the body

Asymmetric arm or leg posturing

Repetitive movements such as rocking, pedaling, or thrusting

Sudden loss of muscle tone or falls

Behavioral and Emotional Symptoms

Sudden fear, agitation, or distress

Uncharacteristic aggression or irritability

Inappropriate laughter (gelastic seizures)

Crying or sobbing (dacrystic seizures)

Bizarre or purposeless behaviors

These behaviors are not intentional and lack organized, goal-directed action.

Vocal and Speech Symptoms

Shouting, yelling, or screaming

Profanity or unusual sounds

Sudden inability to speak

Slurred or distorted speech

Sensory and Autonomic Symptoms

Unusual smells or tastes

Epigastric or rising abdominal sensations

Changes in heart rate or breathing

Sweating, flushing, or drooling

Cognitive Symptoms

Forced or intrusive thoughts

Brief confusion or staring

Difficulty responding despite apparent alertness

After a seizure, some people experience mild confusion, muscle soreness, or emotional changes, while others recover almost immediately.

Why Frontal Lobe Seizures Are Often Misdiagnosed

One of the greatest challenges with frontal lobe seizures is that they don’t always look like seizures in the traditional sense. Unlike parasomnias, however, frontal lobe seizures are stereotyped and look the same each time, are brief, and often cluster. Parasomnias tend to be longer, variable, and associated with confusion afterward.

They may involve:

Thrashing or bicycling leg movements

Pelvic thrusting

Sudden screaming, shouting, or vocalizations

Inappropriate laughter or crying

Unusual body postures

Speech arrest or sudden inability to speak

Because frontal lobe seizures can involve preserved awareness, dramatic movements, emotional expressions, and rapid recovery, they are frequently mistaken for:

Panic attacks

Night terrors or parasomnias

Psychiatric or behavioral disorders

Non-epileptic seizures

Key features that help distinguish frontal lobe seizures include their brief duration, stereotyped presentation, clustering, and frequent occurrence during sleep.

Frontal Lobe Seizure Triggers

Triggers are factors that increase the likelihood of a seizure occurring. Not everyone has identifiable triggers, but common ones include:

Sleep deprivation, one of the most significant triggers

Stress, emotional or physical

Substance use, including alcohol or recreational drugs

Flashing or flickering lights, in some individuals

Illness or fever

Missed doses or abrupt changes in anti-seizure medications

Keeping a seizure diary that tracks sleep, stress, illness, and daily activities can help identify personal patterns and guide management.

Causes and Risk Factors

Frontal lobe seizures can result from:

Brain injury or stroke

Tumors or structural lesions

Infections

Abnormal brain development

Genetic conditions

Unknown causes

Some inherited forms, such as sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy, can run in families.

Diagnosis: Why It Can Be So Challenging

Routine EEGs may appear normal in frontal lobe epilepsy, especially because muscle activity can obscure electrical signals. Diagnosis often requires:

Detailed clinical history

MRI with high-resolution imaging

Prolonged video-EEG monitoring

Sleep studies for nocturnal events

Advanced testing such as MEG or SEEG

For many people, diagnosis is a process rather than a single moment.

Treatment Options

Treatment aims to reduce seizure frequency and improve quality of life.

Anti-seizure medications are typically first-line therapy

Surgery may be considered if seizures do not respond to medications

Neuromodulation may be used when surgery is not an option

Lifestyle strategies, including sleep management and stress reduction, play an important supportive role

Living With Frontal Lobe Seizures

For Ruth, treatment didn’t make everything disappear overnight. But her seizures became less frequent, and she learned how to explain them to herself and to others.

“The hardest part,” she said, “was feeling like people thought I was doing it on purpose.”

Frontal lobe seizures remind us that epilepsy doesn’t always look the way we expect. Sometimes it looks like laughter. Sometimes it looks like fear. Sometimes it looks like behavior, when it is biology. Understanding is the first step toward accurate diagnosis, compassionate care, and better outcomes.

This blog is for educational purposes and does not replace medical advice. If you or someone you love experiences unexplained episodes like those described, consult a qualified healthcare professional for evaluation and care.

Further Reading:

Choose Knowledge: