Understanding Generalized Tonic–Clonic Seizures (GTCS): Mike’s Story

This blog explores generalized tonic–clonic seizures GTCS), previously known as grand mal seizures, through the real-life story of Mike, a teenager whose first seizures appeared during a stressful exam week. The post explains what GTCS are, why they happen, how they’re diagnosed, and what families should do when they occur. With practical tips, clear explanations, and a hopeful message, this article helps parents, teens, and caregivers better understand epilepsy and feel prepared to manage it with confidence.

Dr. Clotilda Chinyanya

11/22/20255 min read

Generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS), previously known as grand mal seizures, are one of the most recognized types of seizures, the kind people often picture when they think of epilepsy. They can be frightening to witness, emotionally overwhelming for families, and physically exhausting for the person experiencing them. But with the right knowledge, support, and treatment, people living with GTCS can lead healthy, full lives. To bring this topic closer to home, let’s begin with Mike’s story.

Meet Mike: A Story Many Families Relate To

Mike was a bright, energetic 14-year-old who loved football, video games, and staying up late talking with friends online. Nothing suggested that epilepsy would become part of his life until one morning, everything changed.

After a week of exams and very little sleep, Mike collapsed in the kitchen during breakfast. His body stiffened, his arms and legs began to jerk rhythmically, and he was unresponsive. His parents watched in shock and fear until the seizure stopped on its own. Moments later, Mike was confused, tired, and unable to recall what had happened.

A second event occurred a few weeks later following another late night. This time, his parents took him to the emergency department, where a neurologist explained that Mike had experienced generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and that fatigue, stress, and screen overuse may have triggered them.

The diagnosis was life-changing, but it also opened the door to understanding, management, and hope.

What Are Generalized Tonic–Clonic Seizures?

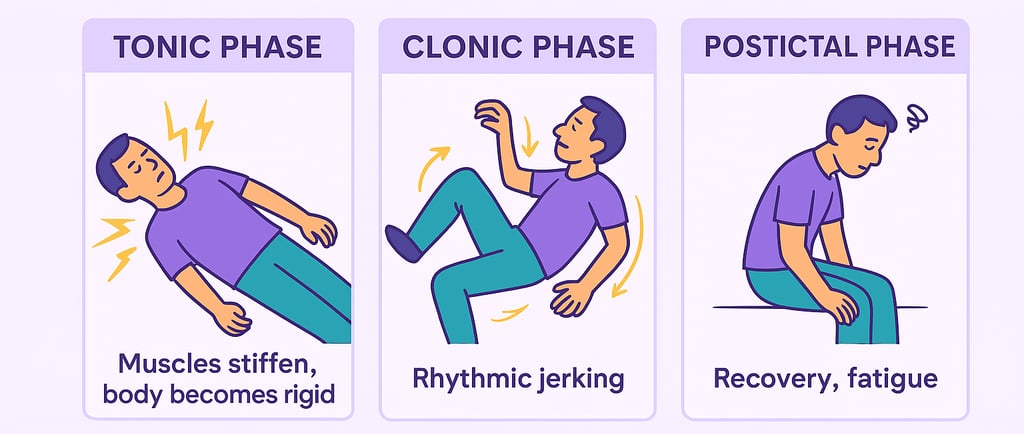

Generalized tonic–clonic seizures involve a loss of consciousness and progress from a stiffening phase (tonic) to a rhythmic jerking phase (clonic), though variations in this sequence can occur. Epileptic seizures occur unprovoked. GTCS affect the entire brain (both hemispheres) from the start of the seizure. Some people get warning signs (aura) alerting them of an impending seizure. GTCS typically occur in two phases:

Tonic Phase

Body stiffens

Breathing may become irregular, resulting in a cry or groan

Eyes may roll back

Loss of consciousness

Clonic Phase

Rhythmic jerking of arms and legs

Possible drooling or tongue biting

Loss of bladder control in some cases

The seizure usually lasts 1–3 minutes.

Anything longer than 5 minutes is considered a medical emergency.

Afterward, the person enters a post-ictal state, marked by:

Confusion

Headache

Deep fatigue

Memory gaps

Emotional sensitivity

This phase can last minutes to hours.

Common Causes of GTCS

GTCS can occur on their own or as part of a known epilepsy syndrome. Most common causes include:

· Genetic generalized epilepsy (genetic/idiopathic)

· Epilepsy due to structural brain abnormalities

· Epilepsy due to infectious causes

· Epilepsy due to metabolic disorders

· Epilepsy due to immune-related diseases

Common Triggers of GTCS

Some common triggers include:

Sleep deprivation (like Mike before his exams)

Stress and emotional strain

Flashing or flickering lights

Skipping medication

Illness or fever

Alcohol consumption

Dehydration

Many teenagers have their first generalized tonic-clonic seizure during times of rapid growth, hormonal shifts, or increased stress, as these changes can disrupt the brain’s electrical balance. Seizure triggers vary from person to person, so it’s important for everyone to learn what factors may contribute to their own seizures.

Prevalence

Seizures:

· Generalized tonic-clonic seizures usually start between ages 5–40, most often in teens and young adults (11–23 years).

· Most common in infants with febrile illness and adults over 75 due to structural brain disease.

· About 20% have a family history of epilepsy, and around 10% have relatives with febrile seizures.

· The genetic cause is unclear; the CLCN2 gene is rarely linked, and other genes may be involved.

· Neurological exams, development, and cognition are generally normal in this syndrome.

· Make up about 1–2% of emergency department visits in the U.S.

· Approximately, 11% of Americans experience at least one seizure in their lifetime.

· Occur more often in males

· Higher emergency-visit representation among African Americans

Disease Mechanisms

Seizures develop when the brain’s balance between neuronal excitation (glutamate) and inhibition (GABA) is disrupted.

How GTCS are Diagnosed

Diagnosis involves a combination of:

Medical History

· Doctors ask about the events leading up to the seizure, what witnesses observed, and any past neurologic symptoms.

· Physical examination

EEG (Electroencephalogram)

This test records brainwave activity and often shows generalized spike-and-wave patterns.

MRI Scan

To rule out structural causes such as tumors, malformations, or scarring.

Blood Tests

To check for metabolic problems, infections, or medication levels.

A diagnosis of epilepsy is usually made after two or more unprovoked seizures.

Alternative Diagnosis

A correct diagnosis is critical because not all seizures are epileptic seizures. Conditions like syncope, transient ischemic attacks, non-epileptic seizures, migraine, sleep disorders and paroxysmal movement disorders all mimic GTCS. Giving a wrong diagnosis, leads to wrong treatment.

How GTCS Are Treated

Treatment is personalized but usually includes:

a. Anti-Seizure Medications (ASMs)

Medication aims to reduce or eliminate seizures while minimizing side effects.

b. Emergency Medications

If seizures cluster or last too long, rescue medications may be prescribed.

c. Additional Therapies

For drug-resistant epilepsy:

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)

Ketogenic diet

Epilepsy surgery (rarely for generalized epilepsies)

d. Lifestyle Adjustments

Regular sleep schedule

Stress reduction techniques

Avoiding known triggers

Staying hydrated

Limiting alcohol

What Families Should Do During a GTCS

Knowing how to respond can save lives.

DO:

✅ Gently roll the person onto their side

✅ Cushion their head

✅ Loosen anything tight around the neck

✅ Time the seizure

✅ Stay with them until fully alert

DO NOT:

❌ Do not put anything in their mouth

❌ Do not try to restrain movements

❌ Do not give food, drink, or medication until fully awake

❌ Do not panic — stay calm and reassure others

Call emergency services if:

The seizure lasts more than 5 minutes

It’s the person’s first seizure

They have difficulty breathing afterward

Another seizure begins immediately

They are injured during the seizure

Complications of GTCS

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures are linked to higher risks of:

o Psychiatric and cognitive problems

o Sleep disturbances

o Cardiovascular and bone-related conditions

o Physical injuries and early death

· Frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures are the strongest known risk factor for SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy).

· While there is no guaranteed prevention, maintaining good seizure control and having nighttime supervision may help reduce SUDEP risk.

Mike Today: A Story of Strength and Awareness

With proper diagnosis, medication, lifestyle adjustments, and support, Mike’s life gradually stabilized. His seizures became rare, his confidence returned, and he learned how to manage his sleep, stress, and screen time. His family learned how to respond safely, how to support him emotionally, and how to normalize his condition without limiting his independence.

Mike now shares his story at school assemblies to help other students understand epilepsy, turning his hardest moments into an opportunity to educate and empower others.

Final Thoughts

Generalized tonic–clonic seizures can be intense and frightening, but they do not define a person’s life or potential. With awareness, timely diagnosis, proper treatment, and community support, teens like Mike can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

If your child or loved one experiences seizures, remember:

💙 You are not alone.

💙 Epilepsy is manageable.

💙 Knowledge and preparedness make all the difference.

References & Further Reading:

Cleveland Clinic - https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22788-tonic-clonic-grand-mal-seizure

Cognitive Functions and Epilepsy - https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186/s43045-023-00293-6.pdf

Epilepsy Foundation - https://www.epilepsy.com/what-is-epilepsy/seizure-types/tonic-clonic-seizures

ILAE -https://www.epilepsydiagnosis.org/seizure/tonic-clonic-variants-overview.html

John Hopkins - https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/epilepsy/tonic-clonic-grand-mal-seizures

Mayo Clinic - https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/grand-mal-seizure/symptoms-causes/syc-20363458

Mount Sinai - https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/diseases-conditions/generalized-tonic-clonic-seizure

National Library of Medicine - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554496/

University of Southern Denmark - Epilepsia, 65(1), 84-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17809

Choose Knowledge: